Although the Maypole was a late addition to Ireland’s May Day celebrations, never gaining the widespread observance of the many older beliefs, customs and festivities associated with Maytime, the Maypole did enjoy local popularity in certain districts between the seventeenth and the nineteenth centuries. Introduced and originally popularised by English and Scottish settlers in the years following the plantations of the sixteenth and seventeenth Centuries, Maypoles could previously be found in prominent positions, particularly in towns and villages that lie near the east coast of Ireland. A couple of centuries ago Dublin could boast of having at least three Maypoles; one was situated in the centre of Harold’s Cross Green, while Dublin’s principle Maypole was planted near the Botanic Gardens on the north side of the city, and a third Maypole could be found in Balbriggan in North County Dublin. Outside of Dublin Maypoles could be found in the towns of Kilkenny, Downpatrick, Mountmellick in County Laois and Maghera in County Derry, as well as in the villages of Kilmore in County Down and at the cross-road Castledermot in County Kildare.

Today the village of Holywood in County Down can lay claim to having the only surviving Maypole in Ireland. On the first Monday in May each year the pole is still decorated with ribbons, a May Queen is crowned and groups of local school girls dance around the Maypole, while large groups of spectators enjoy the festivities. An information notice in the town notes that a Maypole has stood at the cross-roads of Holywood since 1620, a fact that was established on an old map – making the Holywood’ Maypole the first recorded Maypole in Ireland. A local legend explains how the original pole was first installed in the town. The legend maintains that a ships mast, was given as a gift to the people of Holywood as a gesture of gratitude for the hospitality and assistance they provided to a crew of Dutch traders who were shipwrecked off at Belfast Lough near the town. Since the first pole was planted at the cross-roads in Holywood nearly four hundred years ago replacements have been required at various times, in 1943, for example, a storm toppled the Maypole which nearly collided with a passing bus. The current Maypole, in the photograph above, stands at a height of 55 feet without the weather vane atop.

Like the Maypole in Hollywood many of Ireland’s Maypoles were permanent – standing all year round, and used for a wide variety of purposes which included; as an assembly point for the local population, as a flag-pole, to post local news or bills, or as a weather-vane. Additionally Maypoles were often decorated to mark special occasions throughout the year, the pole at Holywood, County Down, for instance, was previously, and possibly still is, adorned with orange and blue flags and streamers on the twelfth of July in celebration of the Battle of the Boyne, while in the early eighteen hundreds the Pole in Glasnevin was painted white with blue and red spiral stripes on Easter Monday each year.

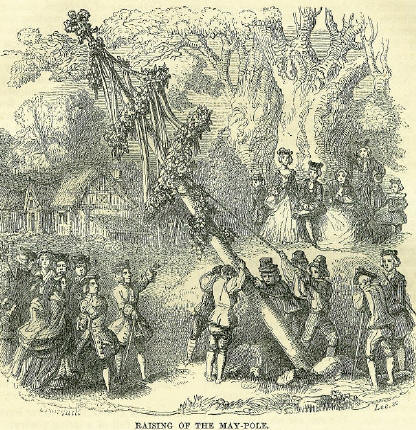

Many traditional amusements and customs were carried out by those who assembled at May Poles on May Day. In Carrickfergus in County Antrim the newly elected May King and Queen took an active part in the amusements by dancing round the pole with their subjects. While at the May Pole near the Botanic Gardens in Dublin the newly elected King and Queen of the May presided over the games with a man dressed in highlander clothing acting as their attendant. Amusements around this Maypole were not limited to dancing, as illustrated by William Wilde’s account of the many boisterous activities which included:

‘running after a pig with a shaved and well-soaped tail, which was let loose in the middle of the throng; grinning through horse-collars for tobacco; leaping and running in sacks; foot races for men and women; dancing reels, jigs and hornpipes; ass races, in which each person rode or drove his neighbour’s beast, the last being declared the winner; blindfolded men trying to catch the bell-ringer; and also wrestling, hopping, and leaping.’

William Wilde also mentioned that in the early decades of the nineteenth century the Maypole ‘was not decorated with floral hoops or garlands like the usual English May pole, but was well soaped from top to bottom in order to render it more difficult to climb; and to its top were attached, in succession, the different prizes, consisting generally of a pair of leather breeches, a hat, or an old pinchbeck watch. Whoever climbed the pole and touched the prize, became its possessor.’

A number of accounts from previous centuries seem to indicate that Maypoles were not exclusively positioned in public locations. Domestic Maypoles seem to have been popular in certain rural areas, for example, in 1682 Sir Henry Piers indicated that the people choose between bush and pole according to their local circumstance; ‘in counties where timber is plentiful, they erect tall slender trees, which stand high, and they continue almost the whole year, so a stranger would go nigh to imagine that they were all signs of ale-houses, and that all houses were ale-houses.’ While Mr. and Mrs S. C. Hall mentioned a wedding tradition were a Maypole was planted outside the dwellings of newly married couples; ‘the first May day after the wedding it is customary for the young men and maidens of the Parish to go into the woods and cut down the tallest tree, which they dressed up with ribbons, placing in the centre a large ball decorated with variously coloured paper and gilt.* They then carried this in procession to the bride’s house, setting it up before the door, and commenced a dance about it which lasted all day.’

The decline of Maypole can be traced to a number of acts dating from 1698 prohibiting their erection, but it was in the aftermath of the rebellion of 1798 – at least in folk memory, and presumably to discourage public assemblages, that British authorities went about removing a number of May Poles. The Reverend John Graham of Maghera in County Derry noted that the long standing tradition of planting a May Pole every year at the market place abruptly ended in 1798, and that even when the tradition was revived, some fifteen years later ‘neighbouring magistrates’ came ‘into the town, and cut down the pole.’ While an article from the 1906-08 Journal of the Kildare Historical and Archaeological Society recorded that the permanent May Pole which stood at the crossroads in Castledermot was cut down after 1798, but not before, as local memory recorded a century later, a number of rebels were hung from the pole.

* Many of the features including the decoration of the tree and the connection with weddings will be familiar to those with a knowledge of the May Bush traditions in Ireland.

Sources

Fergus. ‘May-Poles’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 1855.

Mason, William Shaw. A Statistical Account or Parochial Survey of Ireland. Dublin, London and Edinburgh, 1814-19.

Hall, S.C. (Mr & Mrs). Hall’s Ireland, 1842

Omorethi. ‘Customs Peculiar to Certain Days, Previously Observed in County Kildare.’ Journal of the Co. Kildare Archaeological Society and Surrounding Districts V (1906-1908), 439-454.

Piers, Sir Henry, A Chorographical Description of the County of West-Meath, A.D. 1682

Wilde, William. Irish Popular Superstitions. Dublin 1852.

Williams, Fionnuala Carson. ‘Maypoles on the ‘Road to Richhill’ and Beyond’, Folklife, 49:2, p. 125-149.

Top photograph the Maypole in Holywood, County Down taken by Nev Swift.

The only May Pole I have seen (in Reynoldston, a small village in Gower, South Wales) there were small children dancing around it. I didn’t realise that that people also used a greasy May Pole for a climbing competition (as in Benjamin’s Disreali’s famous quote on becoming English Prime Minister). Do you think authorities were keen to ban them after 1798 to avoid rowdy gatherings that could turn rebellious?

LikeLike

In the aftermath of the 1798 Rebellion gatherings in Ireland were severely restricted. If I remember correctly the laws were to stop Irish people gathering in large groups. Festivals and patrons would have come under particular notice as these holidays and holydays were days were large crowds gathered together. In terms of the Maypole I have direct evidence of the Castledermot and the Maghera Maypoles being taken down as a direct result of 1798

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder if similar laws were passed to prevent Scots gathering after the United Scotsmen failed efforts at insurrection in 1797? Family lore suggests that a distant ancestor of mine, David McEwan, a linen weaver of Dundee in Perthshire, changed his name to Cownie to distance himself from family members who had been involved in sedition.

LikeLike

Ah, thanks so much, and thanks for sharing on your own page too

LikeLike